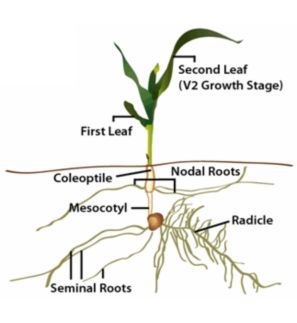

Stresses that impede nodal root development may be caused by living (biotic) organisms such as insects or diseases or by non-living (abiotic) physical or chemical factors such as soil obstructions, soil moisture conditions, cool temperatures, or fertilizer placement. Stresses may be continuous in the field, or may occur sporadically in microenvironments throughout the field.

Continuous or uniform stresses that affect plants equally often include cold or wet soil conditions or below optimum air temperatures. Although detrimental to crop growth and sometimes yield, these stresses are generally less damaging than sporadic stresses that affect one plant and not its neighbors. This is because individually affected plants are likely to fall behind in physiological growth stages if conditions remain unfavorable.

Once a plant begins to fall behind by two or more growth stages, it becomes increasingly difficult for the plant to catch up. This is commonly thought to be a consequence of shading by its competing neighbors. Shading slows the plant's growth rate, further reducing root elongation and nutrient uptake. Thus, the problem of competing for limited resources is compounded, likely for the remainder of the plant's life cycle.

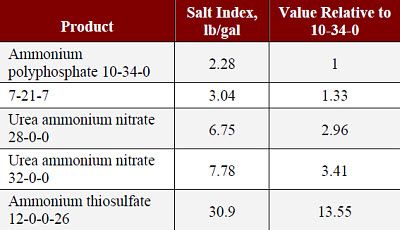

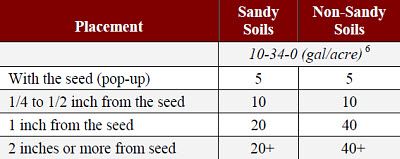

Sporadic or variable stresses in a field can be more detrimental to grain yield than continuous stresses. Sporadic stresses include: uneven residue distribution, dry or cloddy soils, wet spots, diagonal anhydrous ammonia bands, fertilizer salt injury, wheel traffic compaction, seed furrow (sidewall) compaction, insect or herbicide damage to roots, and soilborne diseases.

Uneven stands have been reported to suffer corn grain yield reductions from six to as much as 23 percent depending on the severity (Nielsen, 2010; Nafziger, et al., 1991). This yield loss could be significantly reduced by starter fertilizer applications in cases where the primary cause of uneven stands is the inability of the young nodal root system to access sufficient soil nutrients.